There are few images as unusual as that of two respected medieval historians fighting for the pisient count in the famous Bayeux tapestry, that enormous work of art of the eleventh century (its first record is, however, of 1476) 69 meters long, which represents the events that led to the Norman conquest of England in 1066.

Oxford Academic George Garnett decided to count in 2018, for entertainment of his colleagues, the number of penises in the fabric. He concluded that there were 93: 88 of horses and five other human beings. He published it in an article in the magazine History Extrabelonging to the BBC and, as always that a renowned historian speaks of medieval penises, the virility of the networks made it viral. Now, Dr. Christopher Monk, a tapestry student and an expert in “Anglo -Saxon nudity”, as the known as the known as Medieval monkhe affirms that there is one more: “I have no doubt that it is a representation of the male genitals; let’s say it is the missing penis. The detail is surprising from the anatomical point of view.”

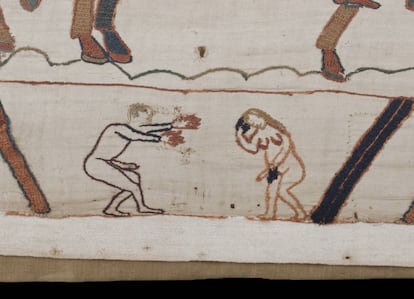

The fruit of discord is found in the lower margin of the fabric. It is a man running with a sword in each hand and with a lump, black and with a tip between yellow and pink, hanging under his robe. Garnett is clear that it is the pod in man’s dagger because “just at its end there is a yellow spot”, which he defines as brass. “If we look at what are unquestionably penises in the tapestry, none of them has a yellow stain at the end,” he said in the podcast History Extra, where the duel of medievalists.

But his colleague says that brass is a glans, and has a theory to confirm it. As he explained, “some of the stitches seem to be original: the pale thread of the circular testicles and possibly the tip, or glans, are; the black stitches of the axis are, however, a subsequent restoration.” That is, behind that black thread, perhaps with a not very good restoration, is the lost member of the tapestry.

In any case, beyond the easy joke, the Bayeux tapestry – which is actually an embroidered linen fabric – is “one of the great works of art that preserve themselves from the Middle Ages” and “by far the most splendid and large textile art that is preserved” of the period, Garnett explained in the podcast. The almost 70 meters of fabric that are preserved – others looked at some time – can be explored, in high quality (and tell what you want to count), on the website of the Tapiz Bayeux Museum. The physical space, located in Bayeux, a medieval city in northern France, will close in September this year for restorations and will not reopen until 2027.

A count “neither obscene nor fool”

The fabric is also one of the most relevant medieval documents in history and for its size and the amount of stimuli it offers has been subject, for years, the obsession of many historians. Because of being told, everything has been counted: 626 characters, 202 horses and mules, 560 animals of other species, 37 castles and civil buildings, 37 trees, 41 ships … The particular count of Garnett, according to the researcher, “is neither obscene nor fool” and helps “understand how people thought in the past.”

But then what do the tapestry penises tell? The history of the conquest by Guillermo I is narrated in the central panel of the fabric. The upper and lower margins contain decorative elements, real and mythical animals and scenes that, a priori, do not seem to have any relationship with the main narrative. That’s where penises are. Garnett coincides with the argument of a colleague of his, Professor Stephen D. White, who assured in an investigation he published in 2014 that these scenes on the sidelines are literary allusions to the Latin versions of Fedro of the fables of Aesop, the classic Greek stories that used animals to transmit moral messages to an illiterate society. “The nudes are not free erotic,” Garnett said, and transmit a message: “In those fables there is always sexual activity that involves betrayal or shame.” That makes him think that who designed it “chose the scenes that directly alluded to what was happening (above) in the main narrative. He suggests that what happens there involves shame, revenge and betrayal.”

Here the size does matter

The other 88 members are in the main panel and are all of horses, curiously the only animals of the tapestry represented with penis. The majority, says Oxford’s academic, are purely anatomical, but the artist who did it especially worried about two, associated with important men: Harold Godwinson – last king of Anglo -Saxon England, loser of the battle – and his winner, Duke Guillermo de Normandía. “It cannot be a simple coincidence that Count Harold appears for the first time mounted on an exceptionally well -endowed steed,” explains the academic. And the member with the greatest difference of all is the one that stands out from the horse that a block of block gives to Duke Guillermo just before the battle. Whoever was the one who designed the tapestry insisted on reflecting the virility of the two protagonists in those of their respective mounts and, as can be seen, did not skimp on their stroke.

“What I have shown is that this is a serious and scholarly attempt to comment on the conquest,” Garnett said. Nothing is known about the designer or who commissioned the tapestry, but one of the theories is that it is a work by Queen Matilde (wife of Guillermo I) and her artisan servants. The academic disassembled the theory in his 2018 article: “Bringing the penises account reveals that the tapestry designer had his own obsession, until then inadvertent. I say his, because it is just the type of thing that will be familiar to anyone who has spent some time in a male school, and seems unlikely that it has been the product of a female mind.” And now, he expanded his argument in the podcast. “Who did it was undoubtedly a lawyer and had read the fables. Of course it is possible that some very educated nun, but is less likely.”

It is now widely accepted that the tapestry was a commission from Bishop Odón de Bayeux to be exposed on the day of the consecration of the city’s cathedral, in 1077, and was destined for a clerical audience. “It is worth asking,” Garnett questioned, “if such scenes would have been considered appropriate to be seen by monks or to accompany an event of the liturgical calendar.” In addition to that there is almost no clerical reference on the fabric. If we believe the English academic theory, the tapestry would have to be interpreted by people with a high level of education to understand their subtleties. Or, as Garnett said, “it may not care that those who see it understood all the allusions, but that it was only having enormous pleasure recreating in their virtuousness.”

In any case, experts agree, it is impossible with the available information to confirm any of the theories. Penises, that seems clear, are there for a reason and, as the academic explained, trying to unravel their meaning rather than a sensationalism is a way of trying to understand medieval minds. Is one more or less relevant relevant? Not probably, although it demonstrates the ability of a canvas of 10 centuries to continue surprising. 93 or 94, the verdict is in the hands of the reader.