Love is so prolific that it also allows you to love a city. At first, Mario Vargas Llosa with Barcelona was an arrow, a brilliant sign. It was in Barcelona where the Nobel Prize for Peruvian literature, who died last Sunday in Lima at age 89, was recognized for the first time that his most intimate dream – being a writer – could become reality.

It happened on Saturday, March 7, 1959, when the Editorial Rocas awarded him the Leopoldo Alas de Narrative Brief Award for his story The bosses. In the magazine Destination They described him as a young student of “between 20 and 22, who is in Madrid pensioned by the Government of Peru in order to get the PhD of Philosophy and Letters.”

The Editorial Rocas gave him 10,000 pesetas and published his first book. “I feel important, famous, immortal: the man is weak, medium, the denial of greatness. He receives the conventional palmada of the darkest reporter, of the darkest Catalan newspaper, about the darkest contest – there is a thousand weekly competitions here, as you know – and it is wide and re -objected as a real turkey,” Vargas Llosa wrote in a letter to his friend Abelardo Oquendo.

Then, step by step, the fruitful love for Barcelona was arriving, which illuminated the boom of Hispanic -American literature. It happened first at the hands of the editor Carlos Barral and the literary agent Carmen Balcells later. They formed a strange and bold alliance, a trio so in love with literature that managed to reinvent her.

“Black enthusiasm”

In the early sixties, Vargas Llosa was fed up that the manuscript of his new novel was rejected by different publishers. Until he decided to send her to Seix Barral on the advice of the Hispanic Claude Couffon, who had explained that its director, Carlos Barral, was “trying to publish modern literature, to open a lot of that world a little rarefied from the Spanish literature of those days,” as the novelist himself recalled once. He did so, and in 1962, Seix Barral awarded him the Brief Library Award for The city and dogsa novel so transgressive and full of rage that broke the seams of the Latin American narrative.

Barral remembers in his memoirs that the reading of that book “had been the greatest and most pleasant surprise as editor: it was the most important manuscript that I had ever seen.” He also recalls that at the end of reading it “a kind of unbridled enthusiasm entered him.”

But the path that led to its publication was not easy. They managed to overcome Spanish censorship thanks to the perseverance of Barral, Vargas himself and to the good work of the professor, philosopher and critic José María Valverde, who had been a career companion of Carlos Robles Piquer, general director of Information and Tourism and Head of Censorship. After reading the novel, Robles agreed to publish it with the condition that a few paragraphs were cut – which did not affect the nucleus of the story, according to its author later – and as soon as Barral could include them again in the new editions without informing the relevant authorities.

That type of courage was decisive. Barral felt above all poet, but his “industrial surname”, in his own definition – the editorial he directed, changing her from top to bottom, was an old family business – had “invested with a certain literary power.” And the prize for the work of Vargas Llosa led its editorial to transform into “a transatlantic literary bridge”, according to Barral. It was one of the strongest platforms of union between the new and groundbreaking Latin American literature with Europe and its editorial and cultural ecosystem.

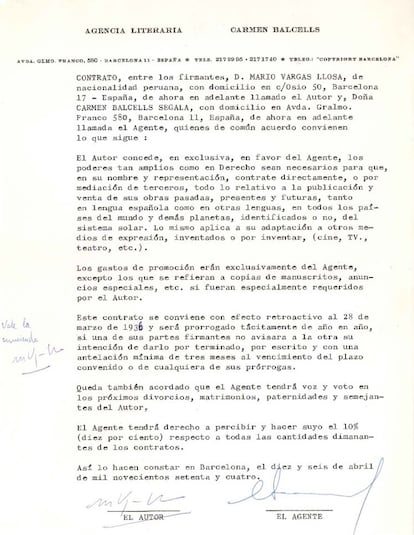

To all these matters was very attentive Carmen Balcells, who since 1960 worked in Seix Barral managing translations and rights abroad. Then, in another unusual movement, Balcells decided that for this literature to flourish writers needed money to devote time to their art and not to work to live. “With a unique vision, the sector revolutionized, betting on representing writers instead of the editors,” explains Maribel Luque, from the Balcells agency.

He did so. In a climate of trust – Balells was later a representative of the work of Barral Poeta, memorialist and essayist -, the Catalan explained the plans to her boss “and he understood (it was, of course, the only editor who could have understood such a thing) and returned his freedom and accepted that, from then on, the editing contracts would be signed by the authors, yes, but the conditions of each contract would She, ”Vargas Llosa revealed.

Change of rules

The rest of the story is already known. The claw of the literary agent started Vargas from the quiet life as a professor at the King’s College and threw him as a writer. In 1970 Balcells appeared at the door of the London domicile to convince him that he had to devote himself exclusively to literature and that the best way to do was moving to Barcelona – to his vera, under his radar – with his wife Patricia and his two children Álvaro and Gonzalo.

Morgana, the little girl from the Vargas Llosa family, was born in the city, because Balcells got what was proposed. He looked for schools for children, a family for the family – first on Balmes Street, then on Osio Street, number 50, in the Sarrià neighborhood, to two streets of another flashing writer, Gabriel García Márquez -, he matched Vargas Llosa the salary he had as a teacher in the United Kingdom and sat him to write his art. “Carmen managed to change the rules of the game, and got the editors to accept it by having behind the strength of authors such as Vargas Llosa or García Márquez,” says Luque.

The Hispanic-Peruvian author always thanked him. And after all, he was a man enfrged by literature and his circumstances. Barral remembered him working “as a possessed,” says Xavi Ayén in Those boom years(RBA, 2014). Ayén also explains that Vargas Llosa and Barral had a great tune, full of private jokes: letters were once written imitating the ancient Catalan of Tirant the WhiteJoanot Martorell’s chivalry novel, a seventeenth -century book.

Before and after establishing itself in Barcelona, the future Nobel spent long seasons in the home of the Barral in Calafell, in front of the beach, and also in the bar that mounted the poet a few meters from his house, L’Esineta. There they lived dinners with goals so long that they once saw the sun rise from under the sea. But at a few hours, there was Vargas Llosa returning to writing, again.

Danae Barral, daughter of the poet, explained to the Diari de Tarragona That in one of his visits the Hispanic-Peruvian writer brought them a small ocelot, a kind of wild cat. As good letter wrapped – now forever – they decided to baptize the puppy with the name of Amadís de Gaula.