The film problem The Brutalist The chair announces it. It is summarized by length chair in the middle of the library. Having an immense window that runs the entire curved wall, who would place the reading armchair in the center of a library?

That first work that signs in the United States, László Tóth, the architect invented by Brady Corbet and his wife, Mona Fastvold – nominated for the Oscar for the best original script – is small, exquisite and ingenious: to prevent the sun from damaging the loin of The books, the shelves fold on themselves. However, the owners do not like, do not pay the order and the architect does not protest and will work at a mine.

Only when the image of that domestic library appears portrayed in a magazine, with the length chair “Inspired in Marcel Breuer’s chairs,” in the center, the owner becomes aware that he owns something special. This sequence summarizes many of the architecture’s problems – a vary in the magazines – and the film The Brutalist. They are not the only ones.

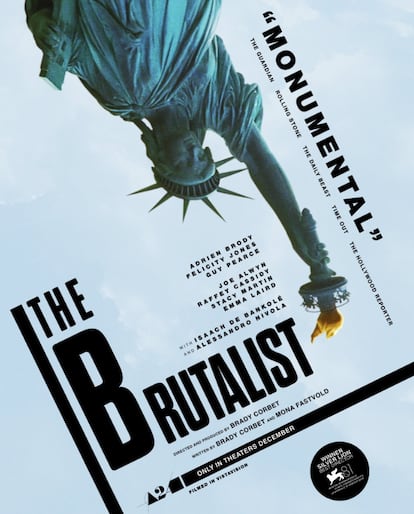

The persecution of the Jews, survival in a field of Nazi concentration, the epic of building a new life, the difficulty of creation, American dream, true love, perseverance, ideals, sexual depravation, a professional relationship Slave, the trip to Italy, the construction of modernity – that is, the reconstruction of the world -, the transforming capacity of art, the power of publications, salvation and ballast of the family, the need for recognition How many things fit In a movie? Make the effort to put them all does not convert a magnificent film. Maybe yes, in Monumental.

Any first work, a first novel, a first article, or the race end of an architect, usually has two types of problems. When these appear by default, that absence portrays a lazy or incapable student. When they are due to excess, the student is usually too ambitious, lacking self -criticism.

The Brutalist It is not Brady Corbet’s first job (36 years) that, with 26 – and after an actor career that had begun with 11 years – signed The Childhood of a Leaderbased on the story of Jean-Paul Sartre, about the hardness of the childhood of the son of an American diplomat who participates in the writing of the Versailles treaty. That first film-already written with her partner, the Norwegian Mona Fastvold-earned her the best debut award and the best director in the 72nd edition of the Venice Biennale. We are not, therefore, before a first -time job.

Why, then, The Brutalist Can it be a more extensive film than intense? Why can it seem lack explanations and, above all, really? Meticulous with the costumes, with recreation – this chromatic – of the time, with the direction of actors, with the design —tipographic and furniture – neglects essential aspects of its main theme: architecture. In that field, errors and anachronisms have plenty, therefore, perhaps, its monumentality, which multiplies its lack of truth, has a lot to do with architecture.

Corbet and Fastvold have talked about surprise and gratitude for the success of the film. Only seven months before starting its distribution there were several companies that declared it impossible to distribute. From there they left. Also of the voluntary ambition that the film will be epic, working with few media. Corbet has produced, at least partially, almost everything he does. One of the milestones that applaud this last film – beyond recovering Vistvision technology, used by Hitchcock, or the dominant matte tone in the 50s – has been its brief budget: 10 million dollars. Thus, the director says that he takes care of each dollar so as not to have to accept commitments with companies. Not accepting commitments is a feat as idealistic as it is laudable. It denotes the same integrity, stubbornness or inability to dialogue from Lászlo Tóth, its leading architect. And so we arrive at the architecture that is where the work contains its greatest errors.

Although there is no film in which there is no architecture of some kind – be it a cave, an airport or a city – very few fiction films have been made about architects. Peter Greenaway’s architect’s belly or the mythical The Manantial, King Vidor’s film based on Ayn Rand’s novel, which will allow me, so much damage to architecture – modern and brutalist – and, I would dare to add, to this movie. Brutalism owes its name to a material, the reinforced concrete –raw concrete In French – that, after World War II, allowed to achieve a new monumentality from the nakedness worked by the Modern Movement. The Franco-Suzizo Le Corbusier was, in addition to one of the first modern architects, the first brutalist. No film has still told his exciting and contradictory life or his undeniable contribution to architecture.

Like Corbet, Greenaway and Vidor mixed in the same architect –guapo, high, quite thin, very tortured, sober and elegantly dressed – a hunger proof ethic, a sense of dramatic creativity and a remarkable sexual attraction. These cinematographic architects are creators, minds obsessed with an ideal: to remove from themselves a great work above resolving with beauty what is necessary for an auditorium, an school, an exhibition or housing to work without destroying the context or exceeding the budget . Precisely because of this obsession for signing a fissure work, these architects were defined as heroic and entire complied with a budget). In this romantic line of obsession with creation, László Tóth acts, the unhappy architect masterfully embodied by Adrien Brody that not only needs to get high to create, but also to dismiss those who work with him, belittling who has another concern that is not the of beauty. With forgiveness, little seems to have learned from Buchenlwald, the concentration camp where he was imprisoned.

That detail also leads to another mistakes of the film: none of the great European architects from the Bauhaus – which, like Toth himself, arrived in the United States from Europe, did so after World War II. They arrived before. Actually, it was the professors who emigrated and none slept in the street: they were so well received that they were responsible for directing the most important architecture schools in the country and, in fact, of changing the way of building in the United States. Thus, Mies Van Der Rohe, one of the last to arrive after closing the school in-in 1933-directed the Illimois Institute of Technology in Chicago, Walter Gropius GSD, the Harvard and László Moholy-Nagy Architecture School founded The New Bauhaus In Chicago in 1937.

Maybe that’s why the film begins as inspired by the survival of Once upon a time in America from Leone and end with a kind of documentary. There are several fragments of real documentaries during the three and a half hours of projection, but the last one is symptomatic. This is an epilogue in which Corbet explains what happened to the leading architect because, perhaps, in the previous three hours he has not had the opportunity to do so. That epilogue contains another error. By 1980, the Venice Biennale, questioned modernity presenting postmodernity.

With everything … there are more architectural problems: the buildings that Toth had signed in Budapest are bastards, mixtures of modern real estate, it seems that produced with artificial intelligence. How that detail affects the integrity message defended by cape and sword does not seem to disturb the director. Nor the final nonsense, the unspeakable auditorium that has justified so much suffering and that we only glimpse at the end. There is only claim, as if architecture were an excuse to achieve something incomprehensibly overwhelming. That the final building is a bad property overshadow the achievement of managing a building without building it, but, even worse: it destroys the thesis of the film. For so much mediocrity there was not so much effort. Corbet needed architecture to talk about the sublime. Do not tell, show it.

In the end, that has been the great defect of much of the architecture of recent times, its formalism, the importance of its appearance above any other factor. Included that the building works. And that, just that, is what seems to defend The Brutalist. And try to do it with a building that is formally disastrous. Why does that effort?

In an interview that can be seen in Youtubethe journalist Simon Mayo gives Corbet that essential basic question. The director replies that he chose architecture because this, like cinema, is a heroic job: he needs money and relationships. “There are almost no films about architects,” he adds.

He does not talk about teamwork. Only epic effort. Thus, there is still a film that does not mitigate architecture. The best architecture is beautiful, but not because it is imposed, it is because it has been able to understand people and root in the place. It is because it has attended to history and has updated tradition. The best architecture helps improve people’s lives. Accompany without imposing. You don’t need to scream. And less, despise.