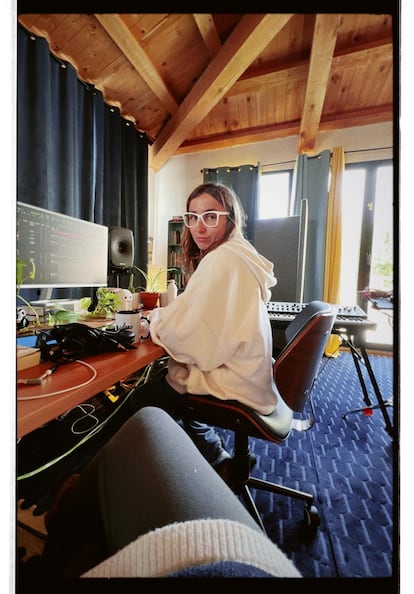

It is quite common for the artistic direction of a female project to be signed by a male name. The figure of the music producer is as important as it is unknown, but above all it is a job that is visibly biased by gender. Zahara (Úbeda, 41 years old) has spent half her life in the recording studio; However, this year she will sign her album as a producer for the first time: Slow tendernesswhich is published on February 21. One of the main drawbacks she encountered in the beginning was that everyone considered the producer to be an external agent, and she herself assumed this belief. “When I lived in Granada, when I was 20 years old, I already produced my models, but no one ever made me see that what I was doing was a production or an approach to production,” the artist tells EL PAÍS. Although she always had a second in command, Zahara was puzzled: “I didn’t understand why I wasn’t being the producer, when many of the artistic and musical decisions had had a first filter that was mine, there was artistic direction on my part. and I didn’t know why I couldn’t continue doing it.”

In January 2024, a study by Spotify and USC Annenberg estimated 6.5% of music producers compared to 94.5% of producers worldwide. Of them, less than 3% have participated in the 800 most relevant songs of the last decade. It is an advance compared to 2022, a year in which production companies only occupied 3.5% of the global count. However, the ratio remains 30 men per woman in the recording studio. The data has been extracted from the rankings American publication annuals Billboard: Of the 1,972 producers who appear on these lists in the last nine years, 64 are women. Of these, furthermore, only 19 are racialized.

The tasks of the music producer vary depending on the professional you ask. Sara Ahmed González (Melilla, 26 years old), doctoral student in the Department of Musicology of the Complutense University of Madrid (UCM), defines production as “the complete process of creating recorded music, which ranges from the first technical and artistic decisions until the last phases of post-production.” This is why many producers include being a performer or arranger among their jobs. Furthermore, with the democratization of art and the rise of technology, artists frequently adopt the role of producers, since the appearance of home recording studios (known as home studio) lowers costs for artists. In this sense, Ahmed emphasizes: “This new paradigm has facilitated the professional entry of many women who in other times would have found it impossible. However, the general lack of knowledge of leading women, added to many other factors, continues to fuel the categorical absence of female producers in the industry.”

Los home studio they don’t need too much space: the Argentine producer Bizarrap began his famous Bzrp Sessions from his room in the family home. The only thing you need to start producing is, in this case, a computer that supports audio editing software (also known as DAWs: some of the most famous are Ableton, Logic or Pro Tools). The most precarious studios can be soundproofed using egg cartons and, if the project includes vocals, microphones can be found from 40 euros.

On the democratization of home studio, Alba Morena (Tarragona, 24 years old), producer and author of the eponymous musical project, confirms that it is one of the reasons why she was able to afford to start in the profession: “I took production as part of composition. I think a lot of girls I’ve known have started out like this too. In other words, either I don’t have the money to pay a producer and I’ll do it myself, or I really don’t want anyone else to give their opinion and I want to have the tools to be able to do it.” Teresa Gutiérrez (Santander, 34 years old), better known by her stage name Ganges, follows the same line of action. She started making demos (test recordings) with Garaje Band, an audio editor with a simpler user interface. In that sense, Gutiérrez also learned the discipline to produce herself: “It is important that, if you want to achieve something, you are in charge. Only in this way will you achieve a result that is as personalized as possible, because your head and your hands are the most direct weapon you have.”

Following this dichotomy between production and composition, for Pablo Espiga (Madrid, 29 years old), a doctoral student at the UCM and whose thesis investigates musical production in Spain, it is this technological revolution that modifies the definition: “Prior to the sixties, Production was the process of recording a record product. The Beatles or Brian Eno were advanced of their time because they used the studio as a musical instrument, but it was after the technological revolution after that decade that the compositional process began to be encompassed within the field of production.” Pablo is the creator of Sonopedia, an open access repository that includes, among others, the main agents of record production in Spain since the 60s.

In the list on the website, only three female names appear: Raquel Fernández, Salomé Limón and Maryní Callejo. The latter was the producer, among others, of Los Brincos, and according to Espiga “she was a hypermodern woman for the time, who in parallel would be like the Spanish George Martin, but she has been very marginalized and her figure is barely known.” Espiga acknowledges that there are many more women than those shown in her file, however “it is a work in progress.” One of the sources of his research is the Discogs website, although he admits that the problem is that “everything before 2000 is barely uploaded to the platform, there is a tremendous documentary void.”

Most likely, many production companies are not even accredited as such, since the figure of women is still associated exclusively with the compositional level and not so much with the technological or managerial level. Morena tells it firsthand: “It was very difficult for me to start producing other people because the people I tried to work with did not consider me a producer.” Something similar is experienced by Paola Rivero (Tacoronte, 29 years old), producer and member of the group Cariño: “During the six years that I have been active with Cariño, I have had the opportunity to be in studies a lot, and it is very complicated that, as a woman, they identify you as producer or engineer. When you are a woman and you are in a studio, it will be taken for granted that your job is composition, coffees or management.”

This is what happened to Zahara with her album Get out (2021), since with the publication of said album it was easy to find the attribution of all the work to Martí Perarnau on the internet: “I made the decision that Martí was the producer, because he discovered the sound of the album and I want to claim his figure”. Even so, he considers that the final sound arises from “joint ideas and our synergy, but we did not say that there were two producers and claim it.” in retrospect It has been impossible. At that moment when I begin to lift up Martí, I begin to disappear from the equation.”

Thus, the four producers interviewed, despite their contextual differences, have three things in common: the first and most obvious is that they all start producing in order to work on their own projects. Alba Morena, Zahara and Ganges are singers and composers of their own songs, while Paola adopts, in Cariño, the roles of guitarist and backing vocalist. All of them see production, in the first instance, as a weapon to achieve autonomy, although they agree that they need to constantly validate themselves within said environment. One thought would go hand in hand with the next, since the lack of legitimation in external environments such as the recording studio is a possible reason why artists take control and seclude themselves in a more private environment. Rivero considers it like this: “That insecurity is typical of women doubting their own abilities. I feel that before starting to study I had the urge to learn absolutely everything about sound and audio to kill that imposter syndrome that I had inside me.”

Alba Morena believes that “we all have that impostor syndrome, even if we are producers with recognition, we will still have that problem.” For Ganges, the syndrome appears “not with my own thing, but when I have considered producing an external project.” Although she is currently working for other musical groups, she states: “I never sell myself as a producer, it is something I do only when they ask me.” That fear of signing the artistic direction of a project as oneself is something that Zahara has classified as “being invisible and making myself invisible.”

In this way, the main problem lies in the lack of references and/or the lack of trust for women to be accredited as producers, despite being at the forefront of decision-making: the most likely thing is not that there will be fewer producers, but those who dedicate themselves to it (more or less consciously) do not appear in the credits with said role. In a new paradigm in which musical production encompasses other types of compositional aspects, the majority of independent artists would, in this case, be their own production companies. The future goal is now to hire those who want to work with more than just their own project.