In 2019, Begoña Garrido (Bilbao, 40 years old) was doing her thesis, with a scholarship from the British University of Reading, on the daily life of Basque women during the Franco regime. She conducted more than 30 long face-to-face interviews with older women, and brought together several focus groups. Between coffee and coffee, between memory and memory, a recurring theme crept into the conversations: exile after the war, forced displacement in his childhood. The separation from the family, the forced trip to a foreign country, the new language, the return years later… Garrido was coming across a story and although he could not include any of that in his thesis, which already had the topic assigned, he Finishing his research he found a lot of stories that pointed in the same direction. Some stories that he insisted on preserving.

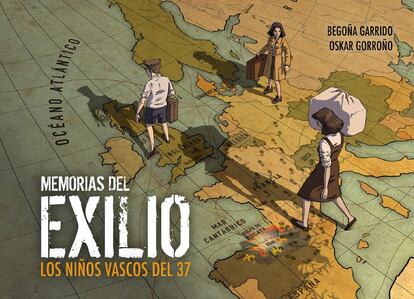

“All families in the Basque Country have some case of children exiled in the war,” says Garrido. She herself had not given it much importance, because her maternal grandmother experienced it with the whole family and, if it was traumatic at the time, little by little it became another family memory. “But during my research I understood to what extent exile was an experience that had deeply marked these people.” And he began to compile the parts of the interviews that narrated the exile into which so many Basque children were forced, forced to leave their homes and families during the war, when the bombings intensified on the northern front. These testimonies, with the help of illustrator Oskar Gorroño, now take shape in the form of a comic: Memories of exile. The Basque children of ’37.

The comic is the translation into image of the real testimonies of several children of that time. Like Martina, who ended up in France at the age of 18; Antonio, who went to the United Kingdom when he was 11 years old; or Lucía, who at 12 had to go to the Soviet Union. These three are the main ones, “but they could be 50 or 1,000,” says Garrido, who recognizes the difficulty of knowing the exact number of displaced children. The historian Xabier Irujo, Garrido recalls, however, speaks of 32,000 children exiled in the Basque Country alone between April and June 1937.

The testimony that surprised you the most during your interviews? “A man. More than because of what he said, because of his silences. They were uncomfortable silences, very difficult to interpret. “Very hard.” The memory of exile brought hidden things to the surface of the interviewees. Many people withdrew from the interviews because they began to have nightmares, says Garrido. Why continue? “Because many are over 90 years old. For my generation they are the grandparents, but for the new generations they are already their great-grandparents, and there is a risk that history will be forgotten.” Garrido found it strange that there were no informative texts about that. “There are academic articles, yes, there are lists in the historical archive, but nothing informative that can bring this history closer to new generations. I felt that either we recovered those stories now, or they would be lost forever.”

And how did the idea of making a graphic novel come about? “What I faced,” says Garrido, was the voice of older people, but what they exuded was the emotion of a child. That’s why I thought about making a comic, which is all emotion.” The meeting with the illustrator Oskar Gorroño came out of the blue. Garrido entered a drawing academy and asked for an illustrator. Gorroño, who had already worked on several comics and children’s books, answered the call, listened to the story, and understood.

“I find it very interesting that we can talk about historical memory like this, because the new generations are not aware of what happened,” says Gorroño. In the Basque Country, he remembers, almost everyone has family stories about the war (his own grandfather survived, but was sentenced to death three times), “and above all, every family has a member who went into exile. “It has become normalized in the houses.”

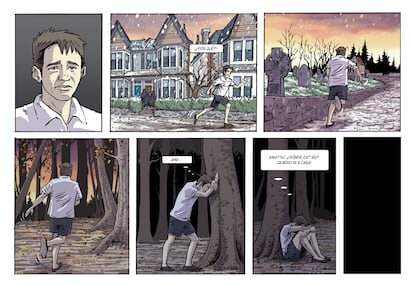

“I have tried, with the drawing, to be restrained. Don’t startle people, don’t be very effective with the inappropriate use of sandwiches and onomatopoeia… it’s a very social story, and the important thing is to talk about the human side,” says Gorroño, who carried out important research work for his drawings, with many visits. to the historical archive and many references taken from photographs, letters and telegrams of the time. “Obviously,” says Gorroño, “exile is not as dramatic as a death on the front, but it is a fact that has repercussions on the entire family, that generates family trauma and that in the end fosters collective trauma.” Gorroño believes that in recent years it has become easier to talk about certain topics.

The curator of the traveling exhibition Spanish seasonal workers in Europe, 1948-1990, Sergio Molina García pointed out to this newspaper on October 22 that, in recent years, “in the study of the history of Spain, emphasis is being placed on blind angles.” He was referring to the small stories that in recent times have rescued the memory of ordinary people, far from the great battles. The comic is no stranger to this. Neck guards, Counterpass, The ballad of the north, The grooves of chance…there are several works that analyze the Civil War, the years before or after it with a focus on the ordinary people who lived through that. Now one more comic joins that list destined to illuminate the darkest corners of memory. Aimed at, as Gorroño recalls, “giving visibility to something that we cannot let be forgotten.”