When Blanca Torres called me to participate in Marisol, call me Pepa I said yes. They put makeup on my dark circles, I reflected out loud about one of the most important Spanish artists of the 20th century and I returned home with that mistrust that we feel every time we collaborate on a documentary. The recording of an interview can last hours and what is collected from your words minimally illustrates what you have said or what you have wanted to say or what you think you have said. When I saw the Verdi in Madrid, Marisol, call me Pepathe resentments passed away.

The film is part of Essential, series of La 2 with which I reaffirm that iconoclasm requires a certain degree of mythomania. Marisol, call me Pepa It stands out for its approach that goes from the girl to the character and from the character back to the woman without insisting on lurid elements that reduce a biography to spectacular morbidity. Any life observed under a microscopic lens is revealed in its eschatological and obscene aspects. Although it is no less true that Pepa Flores’ childhood, puberty, and metamorphoses occurred under extreme conditions. Some shared—Francoism—, others only theirs: a girl singer supports her family and becomes a star.

Blanca Torres escapes from the pornographic logic of certain journalism—also literature and cinema—that, making pain profitable, re-victimizes women who have been subjected to violence in an eternal loop. Torres illuminates the figure of Pepa Flores from her undoubted sociological, artistic, and cultural relevance. The film involves those who know her closely – her sister Vicki -, those who have studied her – Luis García Gil, Aintzane Rincón – and also those of us who have felt that she was within our lives because culture inexorably gets inside us. In the documentary we participated those girls who sang, moving their jaws, and those women admired for the talent and courage that survived precocity. Admired for that loyalty that kept her united to her class and for a political commitment that was not photogenic. For being a woman who managed to emancipate herself from guardianship without losing sensitivity towards the common and the places to which she belongs.

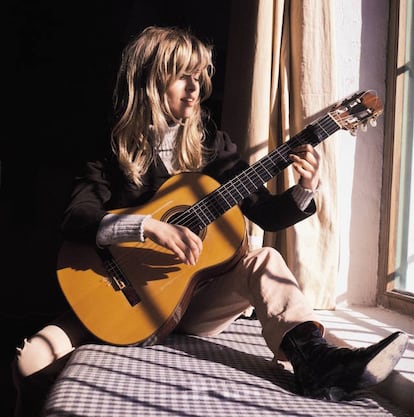

Blanca Torres recovers the images of an artist who mutated in front of the public. Her body was not alien to history, and her nude, beyond commercial vicissitudes, constituted a milestone of the transition: the singing girl of Francoism, the ray of light, the dream that legitimized the darkness of a dictatorship or perhaps gave oxygen to breathe in its stale air, that girl was a naked body against the modesty of repression. However, this revelation also underpinned the usual ideology: women stripped naked by the male gaze, fetishes that break into pieces at the slightest touch. Pepa Flores resists indecent exposure.

His silence is a political silence. His vital gesture is relevant. Marisol as a child was an icon and Pepa as a woman, the different Pepas that followed one another —Tell me about the sailor sea, Mariana Pineda, the Pepa who disappeared—a polysemic and radically coherent matryoshka. The most significant thing is the transformations that happen and flow between the flat icon and the complex icon: the body as a place of crystallization of history, that transition full of conflicting folds that are difficult to freeze in an image. Bodies are outlined, embellished, rot before, against, in history. The successive bodies of Pepa Flores are part of our successive bodies. Blanca Torres, with respect and empathy, assumes the difficulty of telling this movement beyond the clichés.