The Marvel method changed everything in the world of comics. Although he also left some bodies along the way. When Stan Lee launched his superhero publishing house in the sixties, this prolific writer devised a work system that gave him space to publish dozens of comics a month under his signature. The process was as follows: he wrote a brief outline of a script, the artist illustrated it in detail and structured it in vignettes, and then it returned to Lee’s hands to write the text for the speech bubbles. Thus hundreds of ideas and characters were born in just a matter of four years, many still survive. But it also served to forge an eternal enmity between its co-creators. Because, as the works accumulated and the success grew, Lee’s scripts became a single, very descriptive sentence that cartoonists like Jack Kirby (with whom he created The Fantastic Four and The Avengers) or Steve Ditko (in Spiderman or Doctor Strange) would have to develop over the course of a 22-page comic. Soon they claimed authorship, and before the end of the decade, they left the offices. The debates about what each one did extend to today, when their characters are lucrative totems and gods for the masses.

Like someone in ancient Greece who entered temples to worship Zeus or Athena, today visitors can enter the dimly lit corridors of an Ifema pavilion in Madrid to pose with a statue of Spiderman hanging from the ceiling or with the Scarlet Witch behind a lectern. From a room that simulates a classic drawing studio, the exhibition Marvel: Universe of Super Heroes look back at the phenomenon and, through explanations such as how a Marvel comic was created in the beginning, try to understand how this phenomenon was created that today exceeds 40,000 million at the box office and the more than 60 films released in rooms. In addition to being printed on mugs, toys, hotels, clothes… Lee’s decades-long frustrated ambition to jump to Hollywood with that series of The Incredible Hulk from 1977, where one actor played the human and another the monster, whose nostalgic header can be revisited in the hallways of this exhibition.

“None of these characters were born from nothing. They were created by people. And there are hundreds of people working on each film. We wanted to recognize everyone’s work and how that individual creation creates such a massive universe,” says curator Patrick A. Reed, an expert in the editorial that brings the exhibition after passing through the United States and Switzerland and responsible for summarizing 85 years and more of 80,000 characters. They don’t take up much space. It has needed 20 trucks to set up the logistics.

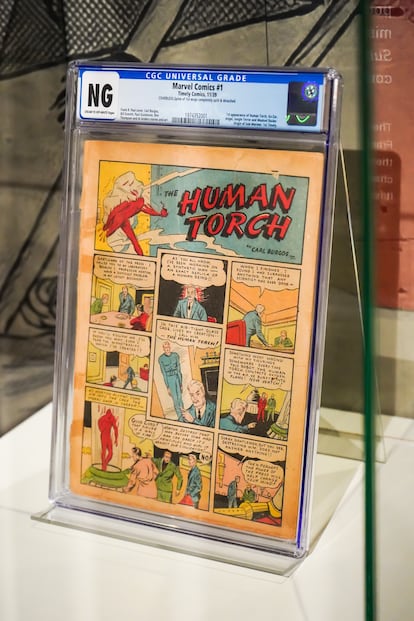

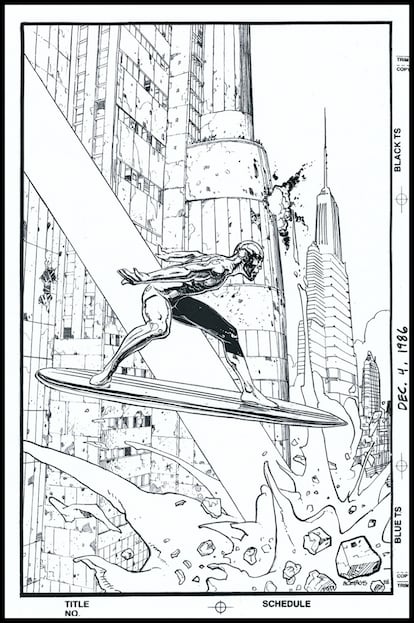

In those trailers came originals like the first Marvel Comics o Amazing Fantasy 15Spiderman’s first appearance in 1962 (a comic that sold in 2021 for $3.6 million); illustrations of Daredevil by Frank Miller and the Silver Stele of Moebius; a typewritten script by Lee, or the banned Twin Towers poster from the first movie Spiderman. They searched collectors’ houses to put it all together. But the original armor from the Iron Man movie or the Wolverine suit in whose fabric you can see the bullet holes were also traveling in boxes. It comes directly from the recent Deadpool and Wolverine and it is a novelty of this exhibition in constant evolution. “When we include a page of Moon Girl and Devilish Dinosaurwe didn’t imagine it would become such a famous children’s cartoon series,” Reed recalls. Of course, Captain America’s shield is not missing either.

All objects are displayed accompanied by explanatory texts that help connect the dots of the creation of each character, although without forgetting the statues ready for the veneration photo on Instagram. They pose for the visitor from the veteran Thing from The Fantastic Four to the much more modern Ms. Marvel, the first Muslim protagonist of the house of ideas. “We wanted the exhibition to be enjoyed on several levels. Children can take a photo with Spiderman and adults can read the explanations,” explains Reed, who built the exhibition on three points: the history of the comic, the explanation of who each superhero is and the relevance of the brand in mass culture. The visitor can spend 20 minutes just looking at the costumes from the movies or several hours understanding the context. And if you like games, you can try the touch screens or interactive spaces (mandatory in any exhibition) such as a flight dressed as Iron Man or the classic arcade machines. pinballwhich will be filled with lines and children for Christmas. Meanwhile, the music that the film composer Lorne Balfe has created for the occasion plays.

Why does Marvel continue to succeed at this level and with such a heterogeneous audience? Reed recalls the company’s classic slogan, “the world you see through your window,” which advocated for the reality of its settings and situations. That is, in his comics there were love soap operas and the real streets of New York were seen. That pure reality today becomes an argument against artificial intelligence: “It is the human and personal part of the creators that made Marvel so successful and why it continues to achieve success. Having characters with problems that you can identify with, even when they are in outer space fighting a cosmic monster.”

That look at what was happening in the world is what made Marvel present a character called Black Panther in the middle of the civil rights struggle or show mutants as “persecuted and hated” through two leaders who reflected the differences in the reality between Malcolm X (who would be Magneto) and Martin Luther King (Professor Xavier). A social reflection that also, as the exhibition explains, made the publisher definitively break with the censorship of the seal of the comic code of conduct.

The Comic Code marked things like “in all cases good will triumph over evil” or that “respect for parents will be encouraged”, it disappeared from its covers when Stan Lee decided to tell the story of Peter’s friend’s drug addiction and monkey Parker, Harry Osborn. The comics went even further when, in the middle of Watergate, Captain America faced the Secret Empire, led in the shadows by a US president who sought absolute power. Next year a movie of the character (now an African-American hero) will show how the current president, with the face of Harrison Ford, becomes a monster, a red Hulk. The exhibition makes it clear that, between explosions and fights, Marvel always had room for the political message, although now many ask that it be separated from entertainment.

“They set out to make diverse comics because they lived in New York and saw people of all kinds on the subway, of all colors and genders. They created a world that resembled their own,” recalls Reed, who from that humanity also tries to explain the confrontation of his creators: “In any creative collaboration, like with John Lennon and Paul McCartney, you have that tension that helps elevate the material. . They are different people with their own perspective on the work, and that gave more layers, more depth and detail. The creation is fluid, because they are also characters that have been developed for decades, changing hands and changing their design, name, story… The Wolverine that we know combines that of hundreds of creators, and each one made him evolve. It is difficult to separate the line, but we must celebrate them all.” Although this also opens a discussion for hundreds of authors who have ended up in poverty after not being paid, despite having created cultural icons known in every corner of the world. The creator ends up being Marvel.

And everything keeps changing, so that everything remains the same. That is the triumph of the Marvel method today, the curator believes: “It is the longest-running serial, a collective work of fiction. For a generation of children, Miles Morales is as Spiderman today as Peter Parker was to me.” And they remain in the collective subconscious, because icons have surpassed the drawing board, and their own creators.