In an orange cardboard box from an English Christmas pudding, the Murcian writer Juan Guerrero kept negatives and photographs from his family album, from his travels through Spain, but, above all, from his friends, for decades. By Juan Ramón Jiménez, Federico García Lorca, Jorge Guillén, Luis Cernuda, Gabriel Miró, Manuel Altolaguirre, Vicente Aleixandre, Rafael Alberti, Pedro Salinas. There is practically no name linked to the generation of ’27 that escapes this archive of images, most of which are unpublished and never before published. The treasure has just come to light thanks to a private donation that, like the rest of the history of these portraits, has been the result of a series of events that go back almost a century in time and that have continued until the arrival, this November, of that orange box at the Ramón Gaya Museum in Murcia.

He has done it with the help of Guadalupe Ríos, an 83-year-old graduate in Fine Arts, illustrator of botanical posters and editorial covers and director of the Plastics department of a school in Madrid, who, in one of those “chances” that he likes to talk about, Juan Guerrero’s widow, Ginesa Aroca, gave him this legacy in the 60s so that “at some point, in the future,” he would “take care of” it. That moment has taken six decades to arrive, also the result of another chance, in which the art critic and historian Juan Manuel Bonet, a personal friend of Ríos, takes part, to whom she showed the photographic archive and told him of her intention to donate it to some public institution. “The Ramón Gaya Museum in Murcia immediately came to Bonet’s mind, because that center had been studying for some time to incorporate the figure of Juan Guerrero into its rooms. It seemed like the perfect place to me: in Juan Guerrero’s hometown; in the museum of one of the artists that Juan Guerrero himself promoted and helped; where the proposal was received with great affection and they were willing to pay attention to the file; in a medium-sized city, where culture is not as crowded as in Madrid, where there are too many legacies and too much of everything,” he explains by phone.

The donation has been welcomed with enthusiasm by the director of the municipally owned museum, Rafael Fuster, who believes that the archive will mark a before and after, both in the history of the generation of ’27 and to highlight the figure of Juan Guerrero, who defines him as “a man of letters in a broad sense, promoter of culture and patron.” Guadalupe Ríos describes him as “the protector of the generation of ’27.” Bonet, as “a chronicler of the world of writers and artists that surrounded him.” But who was Juan Guerrero, so close to that generation of writers in which he has not been included?

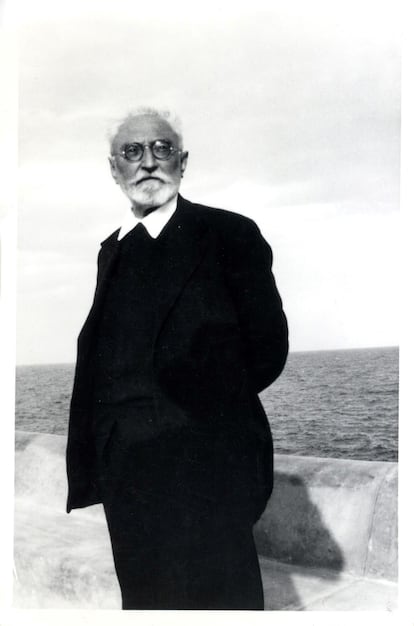

Juan Guerrero was born in Murcia in 1893, he studied Law as a free student at the Central University of Madrid and traveled to the capital in 1913 to meet the poet Juan Ramón Jiménez, fascinated by his literary work. Thus began a relationship of deep friendship that led him to have intense cultural activity for the rest of his life, participating in literary magazines and founding his own publications in his native Murcia: the supplement Literary Page in 1923 and in 1927, in collaboration with the poet Jorge Guillén, the magazine Verse and Prose, which all the great writers of the time went through. It is in that publication where Federico García Lorca writes his first gypsy balladheaded by Romance to the Spanish Civil Guardwhich was accompanied by a dedication: “To Juan Guerrero, consul general of poetry.”

The archive that is now coming to light includes numerous negatives of the Granada poet; in some, portrayed alone, such as one dated 1929 in New York, where he wrote his famous Poet in New York. In other images taken by Guerrero, Lorca appears accompanied by other members of the Generation of ’27 such as Vicente Aleixandre, Jorge Guillén, Rafael Alberti, Pedro Salinas, and even with his little sister, Isabel, who is also portrayed alone in this archive.

The negatives, 1,131 in total, are arranged, placed in envelopes on which, in most cases, the name of the protagonist of the portrait is written. Some also show the date and place where the photo was taken, although many of them are undated. The oldest dates recorded are from 1927 and the latest are from 1953, two years before the death of the writer. The Gaya Museum technicians have made a first classification of the material: there are 567 negatives of landscapes from cities in Andalusia, Castilla y León, Castilla-La Mancha, Aragon, Catalonia, the Community of Madrid, the Basque Country and the Valencian Community. Another 113 images correspond to Guerrero’s own family. The rest are illustrious people, most of them writers, although there are also painters, sculptors or politicians. The archive also includes 33 positive photographs, 14 of them taken at the Madrid Student Residence of the authors of 27.

The director of the Gaya Museum recognizes that there is now an immense task ahead of cataloging all the material that, he assures, will not stop there. The idea of the center is to digitize the material, print part of the collection and carry out an exhibition to which a catalog raisonné will be linked to “do justice” to the great work that Juan Guerrero did for literature and art.

Guadalupe Ríos, who has kept this legacy for six decades, did not get to meet him in person; However, she is linked to him through both her paternal and maternal families, in another surprising stroke of chance among the many that dot this story. A brother of his maternal grandmother, a businessman from Alicante, started a hostel in the Rock of Ifach in the 1930s thanks to the advice and intervention of Juan Guerrero, who at that time worked as secretary of the Alicante City Council.

In one of the negatives in the collection, Guerrero’s children pose with Guadalupe Ríos’ mother in the parador, where other images of illustrious people from the archive were also taken, such as one of Rafael Alberti with his first wife. , María Teresa León, before leaving on a trip to Ibiza in 1936. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War caught the couple on the Balearic island and these photos, never published, are the last that were taken in Spain before go into exile. Guadalupe Ríos knew that history of the parador when years later, in the sixties, she moved to Madrid, to a building on Hermosilla Street that was owned by her paternal grandfather, a native of Aragon. Guerrero had lived there as a tenant for years, his widow continued to live there, and there she gave him that box of English pudding that now makes its contents public.