He writes his memoirs, recites poetry, organizes cultural events and cleans toilets. Leyla, the protagonist of The Applicant (Mapa publishing house), the debut novel by the Turkish Nazli Koca, born in Mersin—so elusive for some questions, that she defines herself as “in her thirties” and about whom photographs are scarce—combines her literary aspirations with her job as a cleaner in a hostel decorated in Alice in Wonderland from Berlin. Leyla is the allegory of so many declassed immigrants and victims of the mirage of meritocracy.

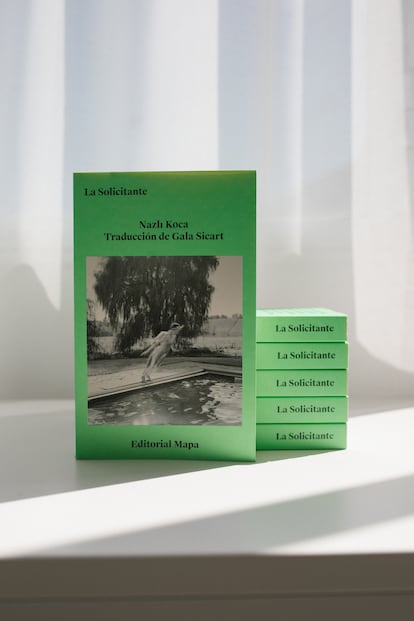

The protagonist is also a transcript of the author’s experiences in the German capital. Koca, also Turkish, addicted to her country’s soap operas, had a complicated relationship with Berlin. She also moved to the German capital to write, disenchanted with Istanbul and her job as a publicist. “Loss, the lack of roots, makes you cling to hope, to the possibility of belonging to a place, even if everything seems lost and things get complicated,” he says in a virtual interview, in which he warned that such Maybe she would connect without turning on the camera. It wasn’t like that. Koca receives smiling from Denver, Colorado, where he resides, with a white shirt; behind him, the Spanish version of his novel, translated by Gala Sicart and published in September.

She has worked as a cleaner, dishwasher or bookseller. She knows disappointment, she has also learned, in her 10 years as an immigrant, that social justice is a fantasy. Under the format of a diary, his novel slaps the reader in the face from the first pages: Alí, a graduate student, unpaid professor with three jobs, Turkish, gives Leyla some latex gloves, along with an eloquent greeting: “Welcome to the “lowest in the immigrant hierarchy.” Koca, like her protagonist, started writing a diary on her first day as a cleaner. “It has been a fun challenge to adapt it into a novel, finding the point between those who expect an exact reproduction of the genre and those who prefer a more elaborate version. The diary today is more than a notebook: it is notes on the mobile phone, Google documents, scattered pages…”, he says.

Leyla loses the right to a student visa after failing her doctoral thesis—by a professor who until then “had approved everyone”—and is trapped in a bureaucratic labyrinth, in a legal category whose name sounds like a joke: Fiction certificate (fictional certificate, in German). If the professor does not change the grade or the court to which he has appealed does not rule in his favor, he must return to Türkiye. However, Leyla does not want to return to a country in a state of emergency where “Erdogan (president of the Republic of Turkey) has all the power to do whatever he wants”, where adults are “lonely addicts” and “young people do not They commit suicide because they are too busy trying to survive.” “When you are a migrant, you have to be either a genius who works at Google, or get married, even if you don’t believe in marriage, so that nationals can see you in the transition to their citizenship,” he says. To overcome difficulties, the narrator applies acidic and cheeky humor.

The title and the letter with which the book opens rewrite the poem The Applicant (The Applicant), by Sylvia Plath. “Give me two coins and I will work proudly in your filthy hospitals, universities, and technology companies. I will live in your apartments and take care of your babies. Free. I will be your cheap whore, here and now,” writes Koca, who avoids social networks. “I recognize their advantages, but, in my opinion, they hinder writing. People become obsessed with getting likes. Another danger is the immediacy of sharing thoughts that have not yet matured, which can hinder the development of ideas and ruin the essence of the creative process.”

The author connects with a genealogy of writers who have unmasked the fallacies of the meritocratic capitalist system: Eva Baltasar, in Decline and fascination (2024); Brenda Navarro, in Ash in the mouth (2022); Noelia Collado, with exhausted mares (2023); Claudia Durastanti, in The foreigner (2020)… Koca triggers experiences while unraveling thoughts. Men “have managed,” he states in the book, “to make us believe that (…) they do not owe us anything after centuries of captivity in their homes, forced to do all kinds of domestic chores without receiving anything in return. How did they achieve it?” “It is impossible to separate the personal from the political. If you check the news on your phone before sitting down to write, it’s hard not to reflect on what’s happening in the world.”

Asked if she is concerned about the extreme right in the European Union and the possible opening of centers outside the EU to expel those who wish to enter community territory, she responds: “The tightening of immigration laws is terrifying. Immigrants are often the scapegoats for all problems. “It is not enough that they are the ones who suffer the most in natural disasters, since they live in tents or cheap infrastructure in refugee camps.”

The protagonist’s class consciousness is strong, a feeling intensified by her journey up the social ladder. From an education in an American school to a migrant cleaner who flirts with sex work, worried about a mother and sister who live with few resources in an apartment in Istanbul.

The myth of Berlin, as a city of opportunities

In The ApplicantLeyla and her friends cling to the myth of Berlin as the city of opportunity where, supposedly, at the beginning of this century you could live for a low rent and flourish artistically and socially. However, the social elevator is broken, even more so if you come from a non-EU country like Türkiye. “Our origin should not give us more human rights, but nationality and citizenship are concepts so ingrained since childhood that even the staunchest defender of human rights finds it difficult to think like this.”

In the midst of chaos and restlessness, the protagonist builds a structure: the “treasures of the day,” objects lost in the hostel that become hers (bottles of whiskey, the novel The wonderful friendby Elena Ferrante, a tracksuit…), her journeys on the U-bahn (Berlin subway), her partying, her relationship with a loving “Swede” who she calls her antithesis (right-wing, with a good position at Volvo in Gothenburg ) and that makes her feel like when she eats “her “mother’s” stew…

Humor and poetry come together in writing. The memory of the pleasant taste of tea is interspersed in the novel with “the stench of vomit, urine and poverty” of Berlin. “Irony works as a shield, it helps maintain sanity, even in difficult moments, such as during the demonstrations in Gezi Park in 2013 in Turkey,” which went from being protests over the conversion of that green space into a shopping center to demand Erdogan’s resignation.

With a naked and biting prose, enlivened by ironic lashes and free of drama, but full of discoveries, The Applicant It is an invitation to embrace life with each of its lights and shadows.