Anyway, I saw myself again in Paris with Gennaro Serio (Naples, 1980), who in his novel Gibraltar night turned me into a murderer. In my meetings with Gennaro, I never find the moment to ask him—I take it for granted—why he chose me as the murderer and why he placed me in Barcelona, at the Gran Hotel Rodoreda on Pau Claris Street, engaged in a discussion with an interviewer at the same time. that I ended up crushing my head.

I know that the time will not come to ask him, because I also converse with Gennaro with endless uninterrupted amusement, not to mention with amazement and admiration for his writing. We talked with joy, as if we wanted to show so many harsh characters today that more “civilized” and currently almost utopian path that is dialogue, the restless talk that would seek what was called “the common well-being.”

But there are plenty of signs that what is civilized, in the strict sense of the word, is broken, like a broken Western dream. There are plenty of signs, although they all seem minimal, like the one I noticed last week in the church of Saint-Germain when spying on the movements of a buzzed group of Asian tourists who stopped in all parts of the abbey to listen to the guide’s detailed explanations about any minute detail of the place, but that, when they paraded in front of the tomb of René Descartes, they passed them by.

Hours later, at the Café Jussieu and after saying goodbye to Gennaro, who was the first to whom I told the “Descartes moment,” I began a long walk along the Seine, bought a newspaper, and sat down at the Café de la Mairie., I read true news and found the article, Unusual suspectsin which Tiphaine Samoyault talked about the novel in which Pauline Toulet had turned the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss into a recalcitrant murderer.

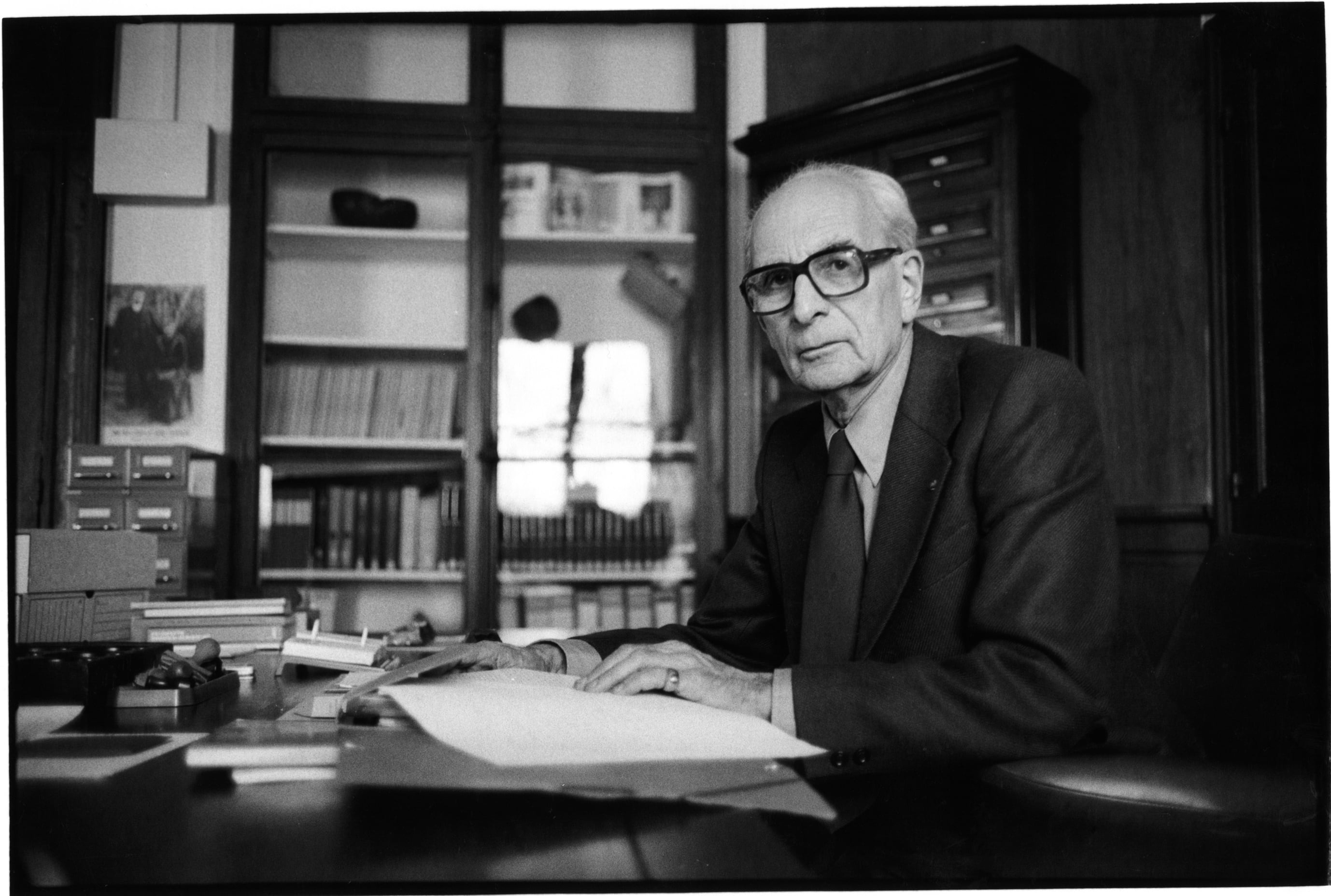

I will not deny that I was pleased with such unexpected company on the list of unusual suspects. I went to the Tschann bookstore and bought the novel, Anatole Bernola and disappeared. The hero, Anatole, was so obsessed with disappearing that he ended up disappearing. Or they forced him to disappear, for having opened an investigation into the uncomfortable story of Lévi-Strauss’s professional rise, whom Anatole saw involved in the strange deaths of his most direct rivals: the sudden fatal collapse of Franz Boas at that banquet of Columbia in 1942 (it fell on top of where Lévi-Strauss was sitting), the end of the great Alfred Kroeber in 1960, and the long silence in life to which Émile Benveniste was doomed in 1969.

Toulet’s novel, with its register so perecquiano (Anatole does not set foot on a single street in Paris that has the letter e), seems like an allegory of how so many reputations in certain circles are built through the murder of some ancestors and the elimination of certain contemporaries. Or perhaps, with some exceptions, is there someone in this entire area who does not defend their territory, seek recognition, define their allies, plan to liquidate their adversaries?