The closet door opened and there she stood: my mother in her worn lilac cotton coat because the wool was so itchy. He tucked a neatly ironed handkerchief into the sleeve of his waistcoat. My mom is dead, but cleaning out her closet was the hardest thing my brother, sister, and I cleaned out this year. Because he was no longer with us, behind the cookie jar in the living room, on his bed in the bedroom. He was in that wardrobe.

Anyone who has lost a loved one knows that clothes are the saddest part of the job called “cleaning up.” Some relatives can’t do that, never. They open the wardrobe door, they feel, they smell – hey, stay with me, forever. Others do the hardest thing first: go, get rid of everything immediately.

American artist Kevin Beasley (1985), now featured in the sensational group exhibition “Unravel” at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, makes the spiritual significance of textiles his signature. Her grandmother and great-grandmother liked to buy their clothes at a store in Harlem, New York, that sold candy-colored scarves, home, garden, and kitchen aprons, caftans, and silk headbands. Beasley still walks into that store in Harlem and buys what her grandmother and great-grandmother might have liked. Since 2015, the artist has been doing what he calls ghost sculptures. He drapes fabric around Styrofoam balls, pours synthetic resin over the fabric, waits until the resin is almost dry, and then removes the balls.

Photos: Artist, Pilar Corrias, London and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich/Vienna

Wall unit with sound

The result is Phased (Flow) from 2017, now on display at the Stedelijk. Phasing is a wall unit with sound. It’s a kind of coat rack where scarves are carelessly hung. This sloppiness is just an illusion: the fabric can no longer move, but is frozen in resin. The void surrounded by scarves resembles the human form: grandmother, mother, ghost – loves flowers and colors red, blue, pink and mustard yellow. Hey, don’t go, Beasley whispers.

Land is an ambitious collaboration with The Barbican in London, where the exhibition was shown earlier this year. The Stedelijk’s basement has collected almost a hundred works by around 50 international artists. All artists use textiles as a medium, but are not necessarily textile artists – a term long associated in the art world with femininity and domestic industry. Thankfully those days are over, so late Land (not the first time by the way).

Already in the 1960s and 1970s, avant-garde artists such as Magdalena Abakanowicz, Judy Chicago, Cecilia Vicuña and Sheila Hicks chose textiles. With a clear cry, they stripped the textiles of their nastiness. These four “primordial mothers” are present at the Stedelijk with monumental, fragile, juxtapositional and abstract works. The oldest participant in the exhibition is the Swede Hannah Ryggen (1894-1970), who in 1966 made a not very sensational anti-Vietnam protest with wool and linen (Blood in the grass). The youngest is self-taught Tau Lewis (1993).

International

Ryggen’s choice also makes the exhibition’s selection criteria clear: they are political. This means that, for example, the great weavers of the Bauhaus (Anni Albers) are conspicuous by their absence. Too abstract? Too little decolonial? The exhibition is also “cross-border” in design. This means that Dutch artists or artists working in the Netherlands are practically absent from the Stedelijk. Represented are Mercedes Azpilicueta, Mounira El Solh and the duo Anthonio Guzman & Iva Jankovic – all but Jankovic from the Rijksakademie. But why doesn’t the Stedelijk also offer a place for the great potential of lesser-known Dutch names? Think Karin van Dam, Joyce Overheul, Afra Eisma, Preta Wolzak, Lidy Jacobs, Bas Koster.

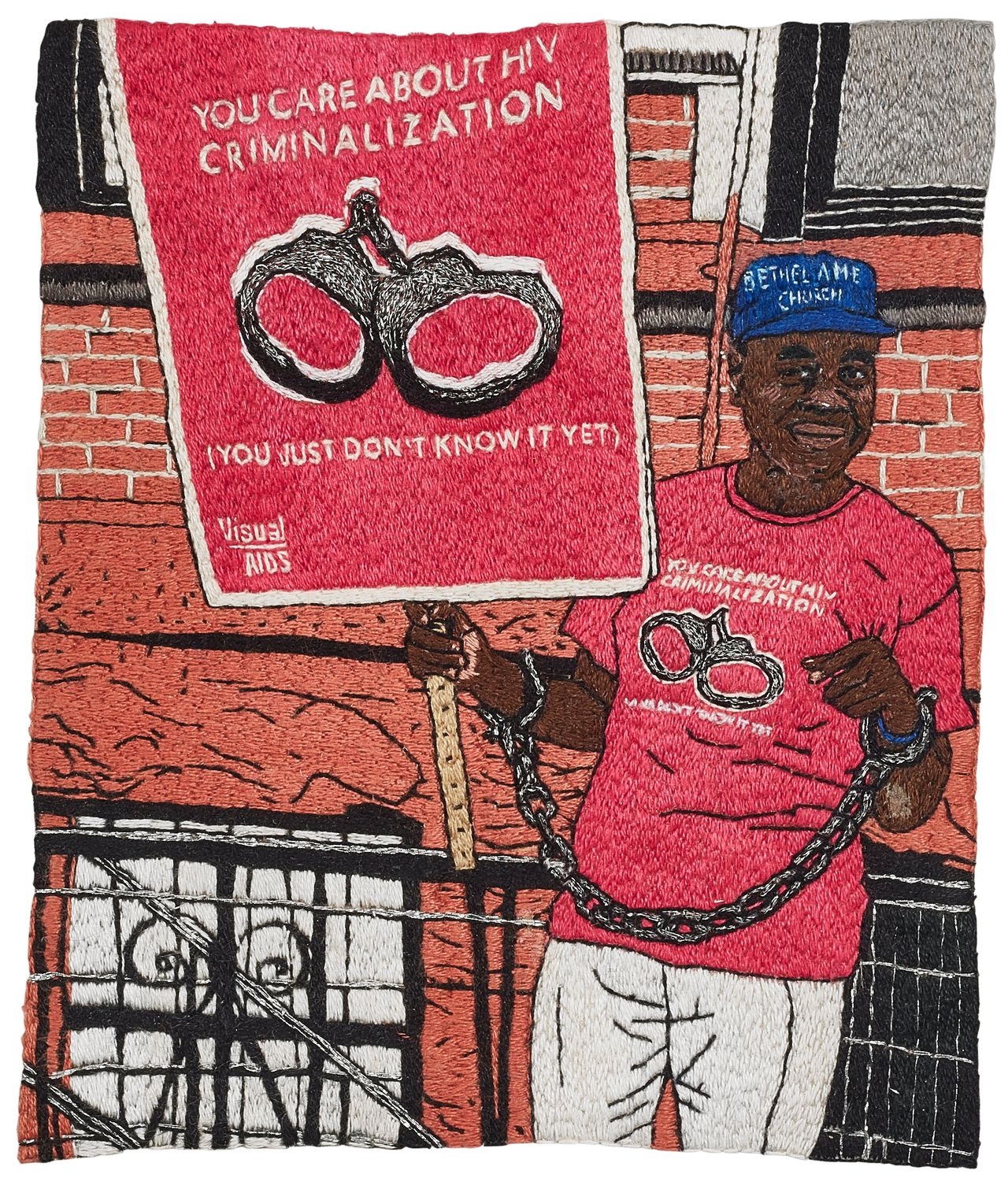

A “subversive stab” based on the feminist art historian Roszika Parker, who died in 2010, is the lead. It shows that a needle, a thread, a piece of string, embroidery can be a tool of resistance Land in every possible way – narrative, dark, violent, soft and fluffy, spiritual and poetic. In order to tame this chorus of voices, a rough division has been made into themes. These themes may overlap. You can also let them go.

Sri Lankan T. Vinoja (1991) explores the trauma of his war-torn homeland in “Borderlands” using beautiful, embroidered and highly abstract aerial maps. Bunker and border in Day (both from 2021). It is not possible to see at a glance what they represent in either work, which makes them so poignant, because war is incomprehensible to those outside it.

/s3/static.nrc.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/26121128/data122242251-e20463.jpg)

All kinds of feathers

Artists from all backgrounds unite under the theme “Ancestral threads”. Not only Beasley, but also the softly fluttering unspun wool of Cecilia Vicuña (1948), conveying ancient knowledge, and the serene weaving works of the American Leonore Tawney (1907-2007). This is also one of many discoveries Land: Tau Lewis (1993).

Born in Toronto but with roots in Jamaica, Lewis displays a tapestry of appliquéd fabrics that incorporate shells. Surface Coral Reef Preservation Society (2019) consists of higgledy-piggledy squares, rectangles and organic shapes. Everything is roughly sewn, technical perfection is not the goal. Underwater animals and parts of black people emerge from this surface. There is a head behind the giant bag’s back, an outstretched hand is caressing the hammerhead. Like the artist Ellen Gallagher, Lewis is fascinated by the potentially poetic side of bitterness Transatlantic voyagea journey that enslaved people from Africa to South and North America, during which about two million people died.

Lewis gives them a grave and a new existence among the riches of the coral reefs, whose existence is as threatened as the black people. It’s science fiction, it’s history, it’s now. All those times are combined with pieces of fabric and shells – seemingly neutral, but full of meaning.

/s3/static.nrc.nl/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/26121121/data122242234-f5ff54.jpg)