The straight line that so orderly dominates the pictorial work of Soledad Sevilla (Valencia, 80 years old) has been transformed for her great retrospective at the Reina Sofía into a circle: the one that traces the circular route – both literally and figuratively – made up of the ten rooms in which the exhibition is arranged, which spans from 1968 to this very year 2024. It is a review inevitably plagued with changes and changes of direction, but as curator Isabel Tejeda highlighted in the presentation of the exhibition, it breathes the “same aroma”: that of a drive, as the artist herself stressed, that has led her to paint, like so many other creators throughout the history of art, “the same painting all her life”.

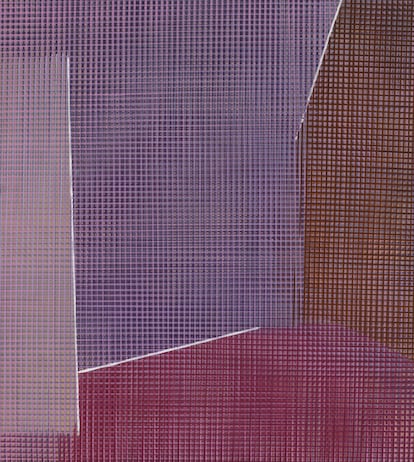

With the title of Rhythms, plots, variables, The exhibition, open until March 10, 2025 (and which will subsequently move to the IVAM in Valencia), brings together a careful, although inevitably partial, selection of the corpus of work produced over almost six decades around the poetic and musical leitmotif of repetition and modularity: a journey that began at the Computing Centre of the Complutense University of Madrid —the space where the first approach in Spain between art and computational technology arose from the hand of artists such as Seville herself, Elena Asins and José María Yturralde, among many others— with stops in other key cities in her career such as Boston and Granada.

Conceived in a chronological sense, the anthology begins in a room where some of the pieces produced at the Computing Centre in the late sixties are exhibited; works that, Sevilla clarified, owe “nothing” to mathematics, of which she declared herself involuntarily ignorant, but to geometry. “At the Centre there was only one IBM computer and some programmers who introduced what we proposed. I proposed working with modules, which I then transferred to methacrylates or fabrics. But that was an arduous process, and I did it faster by hand, so I gave up early,” recalled the painter, who highlighted the best thing about that experience as the contact with the other artists who participated in the experiment: “Being with Lugán, Sempere, Asins, Barbadillo, Yturralde… that was the most interesting thing.”

From those first pieces produced in small format, Sevilla’s aspirations began to turn towards XXL sizes, something that would prove fundamental in her career because, she said, “I am very interested in the painting enveloping the viewer.” And from the apparent cold rationality of technology, the background of her vision began to be tinged with deep emotion and a tireless search for beauty. “She is a truly important artist, one of those who has contributed the most to Spanish painting in the second half of the 20th century,” said Manuel Segade, director of the Reina Sofía, also present at the inauguration. “And she has a spatial understanding of painting that has greatly influenced later generations.”

During his stay in Boston between 1980 and 1982, where he studied thanks to a scholarship, Sevilla conceived and made the sketches of what would later be confirmed as the two most relevant series of his career: The Meninas y The Alhambra. They clearly show the desire that Segade spoke of to represent space from a new perspective, a desire that links his painting with disciplines such as architecture and land art. In the pictures of The MeninasIn fact, the space where the famous Velazquez scene takes place is the only thing that is reflected on the canvas. “In the USA I took some courses on Spanish culture where they explained to us that, through some X-rays of Velázquez’s work, it had been discovered that he did not draw, but simply made references. That direct action moved me,” explained Sevilla. “This painting fascinates us because of the sensation of space it creates, and I represent that space.”

Sevilla is not only interested in large-format pieces, but also conceives its series as large formats. Hence, when entering the room that houses the paintings of The Alhambra The visitor is not only enveloped by each individual work, but by the whole. It could be described as an alternative route through the monument, which the author visited almost daily for “two or three years” always at dusk, when the citadel was closed to the public, to gradually capture its marked transitions between day and night. This obsession, with light and sensory contrasts, runs through other proposals such as her Insomnia Series, The painting was made during her long sleepless nights with the aim of “representing what goes on in my head at that moment.” Unlike her previous works, here the long lines have been replaced by small brushstrokes. The reason? A health problem of the artist, who, unable to move properly, caused the paintings to spin while she was painting. “I have always had Matisse as an example,” she acknowledged, “who went blind and made the wonderful series of cut-out papers.”

Daniel Gonzalez (EFE)

Along with his large series, some previously unpublished pieces from his time at the Computing Centre are displayed along the route, as well as new works and photographic and audiovisual documents of some of his numerous installations, of which, due to space issues, only two are included in the exhibition: one of them produced in threads expressly for the occasion and another made for the Soledad Lorenzo gallery in 1998 and entitled Time flies: A composition full of lyricism that returns, once again, to the idea of circularity through the figure of the butterfly. “It goes from caterpillar to chrysalis and then to butterfly,” the artist noted. “And with this idea I wanted to highlight that the last part of life can be as beautiful or even more beautiful than the previous ones.”

At 80 years of age, the artist receives with this retrospective a well-deserved recognition of her entire career, which adds to recent awards such as the 2020 Velázquez Prize (she received the National Plastic Arts Prize before, in 1993). Like her, Spanish artists of her generation such as Eva Lootz, Carmen Laffón, Concha Jerez or Elena Asins, seem to be repositioning themselves in this 21st century in a central place in the story from which the historiography of the 20th century removed them. “I think that in art it is happening like in society, that now things are being recognized that perhaps ten years ago were not,” responded Sevilla, to give the floor on this issue to Isabel Tejeda, her curator, whose work has been focusing precisely on the recovery of the legacy of women artists who were left on the margins. “Since the 1990s, there has been a generation of historians concerned about this issue, and a great deal of work has been done in this regard, thanks also to the support of museums, galleries and the protagonists themselves,” Tejeda summed up. “It is a great moment of visibility, but it is also true that there is still a lot, a lot of work to be done.”