When Hannah Höch (1889-1978) was 15, she was taken away from school to look after her younger sisters. She grew up in a well-off but conservative bourgeois family in Gotha, Thuringia (Germany), so it was not surprising when seven years later she was allowed to earn a living as a glassmaker by studying at the School of Applied Arts in Berlin. What was surprising was what came next: her short hair, bisexuality, satirical gaze and commitment to the radical avant-garde, to the point of becoming the only woman in the Berlin Dada circle. A display of courage that did not remain within the family, but challenged the whole of society.

It was a time when metropolises were beginning to understand the world through images. Höch worked as a lace and embroidery designer for women’s magazines owned by the muscular Ullstein publishing group. She was financially independent, had existential freedom and was friends with a charismatic artist, Raoul Hausmann, with whom she had an intense and tragic relationship between 1915 and 1922 (he was married and had a daughter; she had two miscarriages). Hausmann introduced her to the circle of artists of John Heartfield and George Grosz, the origin of a new visual language: the technique of photomontage.

The Dadaists proclaimed anti-art, nihilism and a break with bourgeois society and the established order, but each of them claimed personal authorship of the discovery. HH – as she signed her works – was always “the lover of”. The painter and filmmaker Hans Richter denied her artistic recognition with tavern-like audacity: Hanchen She was the girl “who provided the coffee maker, the beers and the sandwiches.”

“From a contemporary perspective,” says Martin Waldmeier, curator of the Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern and responsible for the design of the exhibition, entitled Assembled worldswhich can be seen at the Belvedere Museum in Vienna until 6 October, “the most convincing explanation is that it was a collective discovery, which is the only way to justify the fact that photomontage was developed simultaneously by the Dadaists in Germany and the Constructivists in the Soviet Union.” But he stresses that Höch was a pioneer in giving an artistic, critical use to the avalanche of images arriving from the new mass media.

Among other things, because she knew the publishing world from the inside. One of the targets of her scissors was the media phenomenon of the New Woman. In the cinema and illustrated magazines of Weimar Germany, the ideal of a woman with economic independence, a high education and outside of bourgeois conventions abounded, in contrast to the reality in which most women lived, who continued to take care of the home and the children (paradoxically, Höch was the protagonist of the myth of the New Woman better than anyone else while the Dadaists like Richter saw in her the housewife of the group). The photomontage Made for a party portrays the stereotype of a woman who erases her personality (Höch guillotines her gaze) in exchange for a perfect smile on a perfect body, and who lives under the constant scrutiny of other women (the alien female gaze that Höch sticks in the corner of the collage).

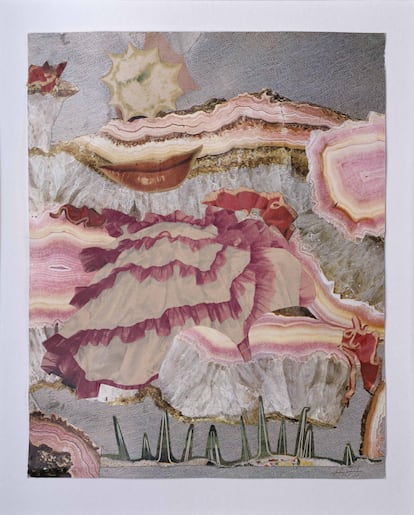

Her rebellion against traditional gender roles went even further. “Pieces like The tamer“,” says Belvedere curator Ana Petrovic, pointing to the 1930 photomontage in the Vienna museum, “can be interpreted as a challenge against gender-differentiated bodies.” “As a praise of androgyny free from social restrictions.” In the pieces Mestizo y German girlwhile deconstructing the recurring cliché of the ideal woman, denounces the ideology of racial hygiene that flourished among the followers of National Socialism. His mockery of the imaginings of purity reaches fabulous heights of creativity and humor in another of his most famous series of montages, From an Ethnographic Museum (1924-1930).

The exhibition features 80 photomontages, as well as a comprehensive selection of the artist’s paintings, drawings, prints and archive material. Her works are displayed in dialogue with the films that inspired her, short films by Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling, Jan Cornelis Mol, Alexander Dovzhenko, Dziga Vertov, Fernand Léger, Paul Painlevé and the Hungarian constructivist László Moholy-Nagy – a decisive influence – transforming the Belvedere into an ephemeral film library of auteur cinema. With a warning at the entrance, more puritanical than necessary: “This exhibition contains historical images that visitors may find disturbing. Explanations of the sensitive content can be found in the respective works.”

When she separated from Hausmann, Höch moved in with her new partner, the Dutch writer Til Brugman, with whom she lived for nine years, a brave act even though it was not prohibited by Article 175. of the Penal Code, which condemned homosexuality in the Weimar Republic. For the legislator, female sexuality was so irrelevant that he did not even consider the option of women being homosexual.

After Hitler’s rise to power, Höch saw the exhibition in Munich until degenerate The walls were hung with the works of many of her friends. From that moment on, none of her works could be exhibited in museums in Germany. During World War II she secluded herself in a low house in the Berlin suburb of Heiligensee, fearing that at any moment the recoil of a Nazi squad would come at her door. The capital of the Third Reich in times of war was not the safest place for a bisexual artist, suspected of cultural Bolshevism and linked to Dadaism, classified as until degenerate; A modernist who had mocked the new racial policies and had her community of affections persecuted or in exile, she was left alone. To her intellectual misery, with her work banned from public life, was added the divorce from the pianist Kurt Matthies, whom she had met on a holiday in the Dolomites. Matthies was 21 years younger than her and mentally fragile. During the marriage he spent long periods in prison for his exhibitionist tendencies.

“By 1937 I had become completely isolated. Even my last friends had left and I could not receive mail (…) Everyone distrusted everyone else, so you no longer spoke to anyone. You forgot the language,” Höch writes in his memoirs. He lived in the home garden where, in fear, he had buried his archive, with his works and those of his Dada colleagues.

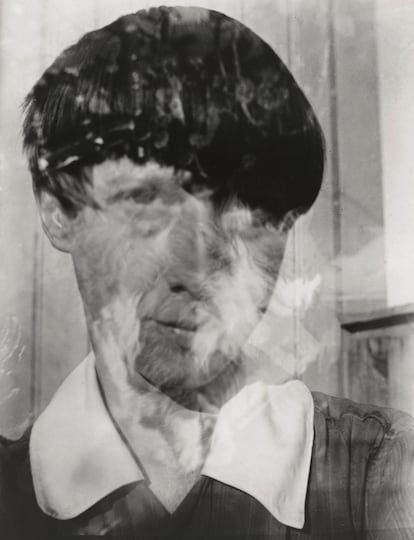

The exhibition reflects how his use of photomontage evolves from a form of rebellion against traditional society to a universal form of visual poetry. In the final section, his masterpiece is Portrait of a life (1972), where for the first time the main subject is her. The last room of the Belvedere, a cabinet of curiosities that holds the greatest surprises, exhibits her collages Surrealists and their “fantastic art”. Hannah Höch died in West Berlin at the age of 88, certain that she was a respected artist. Shortly before, her work as a whole, not only that which tied her to a vibrant group (“I’m fed up with Dadaism,” she said in the 1970s), had been the subject of resounding retrospectives in Tokyo, Paris and Berlin.