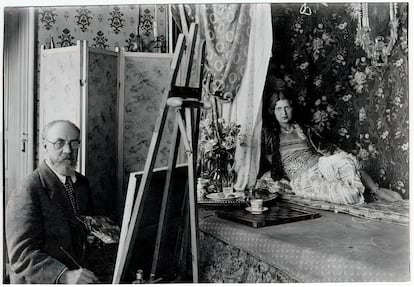

The canvas Odalisque, painted by French artist Henri Matisse in 1920, is to be returned to the descendants of the family of German Jewish textile businessman Albert Stern, who had to sell it during World War II. The painting was acquired in 1941 by the Amsterdam museum of modern and contemporary art -Stedelijk- and its management confirmed this Tuesday the return to the heirs following the advice of the Restitution Committee. It is an advisory body to the Government and considers it plausible that the work served to pay for the Sterns’ attempted escape from Nazi persecution. It fits into the “involuntary loss” contemplated for this type of returns.

The arrival of the painting to the Stedelijk museum is documented and the seller was the Dutch representative of Albert Stern’s textile company. The latter escaped to the Netherlands in 1937 together with his wife, Marie Ebstein, from Berlin. He was of Jewish origin and was fleeing the harassment of the racist policies of National Socialist Germany, but the tranquility did not last long. German troops invaded the Netherlands in May 1940 and occupied it throughout the war, until 1945. Needing money to avoid a new persecution, Stern put Odalisque for sale and the Stedelijk bought it for about 5,000 guilders at the time; about 39,000 euros at the current exchange rate. The escape attempt was unsuccessful and the Stern couple were deported: he died in 1945; she survived and emigrated to the United Kingdom. They had a son and a daughter.

The work has been part of the art room’s collection since 1941, and doubts about its origin have been constant since 2013. That year, the museum itself published an investigation into the origin of the pieces that arrived during the Second World War. Although Matisse painted other odalisques between 1917 and 1930, this was one of the claims of the Stedelijk, which now admits “the sad story it represents due to his subsequent relationship with the unspeakable suffering caused to this family.” These are the words of Rein Wolfs, his director, who has described as a “step forward” the fact of having been able to bring “together with the heirs, this case before the Restitution Committee.” This body, created in 2001, follows the so-called Washington Principles on Nazi-confiscated art adopted in 1998 by 44 countries. Although they are not binding, they help bring together the different national legal systems in cases like this.

Amsterdam City Council is the owner of the Stedelijk collection, and Touria Melani, Councilor for Art and Culture, recalled that “returning works of art such as the Odalisque It can mean a lot to the victims.” “As a city we have a responsibility and a role to play in this.” In 2009, the Dutch Museum Association asked its members to investigate the starting point of their collections to compile an inventory of works with suspicious circumstances from 1933 until the end of the Second World War. It focuses only on Jewish art and ritual objects in national museums and the results have been published since 2013 on a specific website that allows you to consult the history of each piece. In its database there are currently 172 objects considered suspected of having been stolen, confiscated or sold by force. Of the nearly 15,000 files of works lost in these conditions received by the Association, 470 have been returned, according to this website.

Not all objects receive the attention of Matisse’s painting. Or from another, titled Painting with houses (1909) and signed by the Russian expressionist Vasili Kandinsky. Also hanging in the permanent collection of the Stedelijk museum, it was returned in 2022 to the heirs of the Dutch collector Emmanuel Lewenstein, whose son, Robert, had to escape from the Nazis in 1940 to France. His father was a sewing machine manufacturer, of Jewish origin, who had bought the work in 1923 for 500 florins. The Amsterdam City Council acquired it in 1940, at auction, for 160 florins when the Lewensteins had already fled. This case took several turns before its resolution since the involuntary loss of the work by its owner could not be proven. The Restitution Committee declared in 2018 that the family was already in trouble before the world war and the descendants “have not demonstrated an emotional bond with the painting.” On the contrary, the work was “essential for the museum” and did not have to be returned. In 2020, the heirs sued the Consistory and the Stedelijk, and lost the case.

That same year, the so-called Kohnstamm Commission, charged with investigating the Netherlands’ approach to the problem of art looted by the Nazis, concluded that some 3,800 pieces in the possession of the State had their origin in the situation created during the war and downplayed the interests of museums. The City Council endorsed these arguments, and in 2021 it was agreed to return the Kandinsky painting. Delivered in 2022 to the descendants of the Lewenstein family, in February 2023, the Dutch newspaper NRC announced that it had been purchased by a private collector for 60 million euros. He mediated the operation of an auction house.