The French filmmaker Marcel Hanoun (1929-2012) said that his films were for the spectator in the front row, because he does not realize that the room is emptying and that he is alone when the show ends. The repetition of the same shots, a non-sequential montage and the combination of photographs and moving images, elements that make up his cinema, may not appeal to a general audience. He was called by scholars the “grandfather of new wave”; He took the spirit of the time – cheap, free cinema, close to the streets – to an extreme that did not allow him to project a large part of his productions in commercial theaters or be reviewed in the media. However, since shortly before his death, his figure has been revalued in America and Europe by festivals, universities and exhibitions such as the one dedicated to him this Tuesday by the Cineteca de Madrid, on the eve of the screening of his October in Madrid (1967) at the inauguration of the 21st edition of the Documenta Madrid festival, which will be held from May 28 to June 2.

“Hanoun was looking for beauty, but in another part that we are not used to, in the poverty of materials, in films that have other rhythms. It is a cinema that thinks of itself, not only in cinematographic terms, but also in terms of ambition: what cinema can tell,” says the artistic director of the Cineteca and part of the Documenta programming committee, Luis Parés. Despite having become a symbol of marginal cinema, Hanoun achieved success and reach with his first film, A simple story (1959). He received the extinct Eurovision award at the 1959 Cannes Festival, the edition that saw the birth of the French new wave with The 400 blows, by François Truffaut, e Hiroshima mon amour, by Alain Resnais.

Thanks to the notoriety he gained with his debut, they offered him a million-dollar budget to make The eighth hour (1960) with the diva Emmanuelle Riva. The French director, of Tunisian origin, did not like the experience and took refuge in a cinema with minimal costs and over which he had total control, from the script to the editing. “There are too many slaveries with big budgets. Marcel was like a painter in his lonely workshop and suddenly they put 60 people on his team. I know great documentary filmmakers who don’t know how to work with a large staff,” says Spanish director Javier Rebollo, a friend and disciple of Hanoun, whom he describes as extroverted, funny, “with small, watery eyes with which he saw less and less due to diabetes.” ”.

Hanoun later struggled to receive minimal funding from the National Film Center (CNC) or his friends. Godard lent him money to finish his film about Jesus Christ, The truth about the imaginary passion of a stranger (1974). In her last years she filmed without leaving home, with a camera operator, a sound engineer and his farmer neighbor, who made the sets for her. The latter created the models for his short film about 9/11, The Scream (2001), and a couple of objects to reproduce the Middle Ages in Jeanne (2000), a version of Joan of Arc. “He made wealth out of poverty. Her home became a set. People who start making films grow a lot with that,” says Rebollo.

It was precisely in the students where the Frenchman found a loyal audience. In the seventies and eighties he toured universities in the United States and Canada and was a professor at the Sorbonne in Paris. “He is the figure who can help most influence 20-year-olds who are starting to make cheap, ambitious, open films today, a very poetic one that moves away from conventions,” says Parés, who was a student at the Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona. when he met Hanoun at some talks. “For two hours we listened to him, but he was the one who listened to us later, when we went to have beers. “That was the most for a 25-year-old who hadn’t done anything yet.”

That visit to Barcelona was one of many that Hanoun made to Spain, a country he loved. “I liked Spain long before I knew it,” he says in one of his films. He arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in the second half of the sixties, as a correspondent journalist for the ORTF. He was fascinated by mystical poets, mainly Saint John of the Cross. He believed that Castile explained the soul of the Spanish and was in love with Castilian and its diminutives. “It seemed to him that he explained more clearly than the Frenchman,” recalls Rebollo.

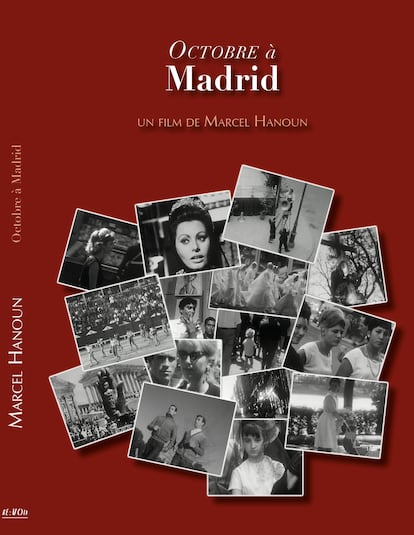

He recorded small documentary pieces, now part of the collection of the Spanish Film Library, about Galicia, Andalusian architecture, Holy Week in Valladolid or the Lady of Elche. But her great love letter to Spain was October in Madrid. The film combines scenes from Madrid – it takes the textbook tour of the Retiro, Gran Vía, Plaza Mayor, the Rastro or the Las Ventas Bullring -, a report on The executioner by Luis García Berlanga and the project he was filming about a woman who lives in the Plaza de Las Comendadoras. “He and Orson Welles are the international filmmakers who have loved Spain the most and have best understood it. The two met her, loved her and filmed her. Catherine Gautier, former director of the Film Library, said that she had done more cycles for Hanoun than for Howard Hawks,” says Rebollo.

Also in Spain, with October in Madrid, Hanoun found the keys that would define his later cinema: films that recount his own filmmaking process, why such a shot was filmed, the setbacks that arose when filming. A kind of behind the scenes loaded with lyricism in which it is not very clear what is true and what fiction. The film begins with a close-up of actress Chonette Laurent and Hanoun asking her sound engineer behind the camera: “Can you hear what you’re talking about, José?” “No, the lady has to speak louder,” she responds. A couple of minutes pass, the phone rings and the person who answers says: “No, Marcel is filming.” Then a voice in off comments: “This movie is about freedom. It ends up becoming beyond all the difficulties encountered, beyond all the contradictions that a filmmaker finds in each scene.”

The idea of making films about films, a meta-cinema, was taken to the extreme upon his return to France with the tetralogy. The four Seasons, on which the Cineteca cycle focuses. Méliès effects, fusion between black and white images with color, music by Bach and Vivaldi and the subjective camera are used to tell stories in which Hanoun enunciates his vision of the art of film-making. “Cinema is a vision in itself,” says the protagonist of Winter (1969), and his producer answers: “Make the distributors and the public understand that.” The same actor, Michael Lonsdale (a constant in his filmography), is creating a scene in front of the camera with the actress Tania in a shot that lasts several minutes in Autumn (1972).

“Do you think they can handle it?” -he asks her.

-Who is it?

―Them, the spectators.

Director Jonas Mekas, another revolutionary of cinematographic language and father of experimental cinema, wrote in the magazine Light: “Marcel Hanoun is the most important and most interesting French director since Bresson. The meaning of Hanoun is cinema. If they don’t like it, they are against cinema. It is lighter than water. At least for me”.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

_