Interior, during the day. A gloomy room with no horizon. Even so, outside you can sense a rural environment, a Spain at the dawn of the 20th century. Sitting in a rocking chair, a mother holds a baby in her arms. Standing, on one side is the father and on the other the doctor, who blurts out, in a native dialect between Catalan and Valencian: “She’s small.” “Sure?” the father responds. And there it is all said. It is the start, and also a declaration of intentions, of bad names the long-awaited first film by filmmaker Marc Ortiz Prades (La Sènia, Tarragona, 46 years old), which premieres this week at the Seville European Film Festival.

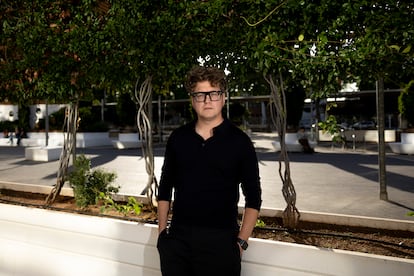

Ortiz Prades—trained at ESCAC, the Escola Superior de Cinema i Audiovisuals de Catalunya—has chosen for his film debut the historical reparation of a real character, an intersex person registered at birth as Teresa—but who could finally die as Florencio—who marked his childhood, when he spent summers at his grandmother’s house in La Pobla de Benifassà, a town of 213 inhabitants in the province of Castellón, with a magnetic mountainous landscape. and brokenness that surrounds the entire film, and that serves as a precise metaphor at the service of history: an isolated enclave with one foot in Catalonia, another in Aragon and another in the Valencian Community; and where its inhabitants, mostly dedicated to shepherding, use a dialect that can sound like Valencian for Catalans and Catalan for Valencians. “There is a value in language and landscape in vindication of identity,” its director explained to EL PAÍS this Sunday, while passing through Seville.

Parallels can also be found in those diffuse borders, when you are nowhere and everywhere at the same time. This is the case of the born Teresa Pla Meseguer, later known as La Pastora and converted during the post-war into the last Valencian maquis. A real figure, but also a legend—very black—for which she was called monstrous “and many other adjectives that I would like not to remember,” Ortiz Prades insists, that this thriller disguised as biopic portrays under the siege of the Civil Guard.

By the time the filmmaker was a child, in Spain in the 1980s, La Pastora had already mutated into a myth: “Don’t be late from the mountain, La Pastora will come and take you”; “Go to sleep or I’ll call La Pastora,” a kind of bogeyman of the area who in reality was nothing more than the scapegoat—his intersexuality was used and manipulated by Franco’s propaganda—to whom the military coup of 1936 and the tremendous subsequent repression of the Dictatorship foisted all the unsolved crimes in the area, “when he hardly knew how to use a weapon,” says the director.

Ortiz Prades, a trained historian, has compiled for this story the oral memory that was part of the town’s routine to strip the official story of its marked hatred of difference: “I wanted to remove the mythology of a monster, of a murderer” and present the character imprisoned within his own body, in a suffocating rural environment and in a polarized, stark and cruel Spain that lived harassed by military power. In fact, the incredible story of La Pastora, formerly Teresa and finally Florencio Pla Maseguer, takes on epic dimensions when, after thirty years living as a woman, she was forced to join the guerrilla – the Valencian maquis – to escape from the Civil Guard. He was the only survivor of his command and, miraculously, he was able to flee to France and start a new life as what he really always was: a man.

The film, however, tiptoes around identity issues, through the contained desire and sexuality of the character. “We wanted to be deeply respectful of Florencio and his story, trying not to judge, but rather understanding his reasons for doing what he does, which is to survive and little else. When the doctor says that the baby is a girl and the father questions everything, everything is said, you already know that there is something strange and there is nothing more to explain. I like to be austere,” says Marc Ortiz, who also signed the film’s script.

This austerity is also carried by the director towards a staging dominated by naturalism, by the choice of the original dialect as the language of the film and by filming in the natural settings where the story takes place. All of this at the service of a chronicle in six acts (which evolves from the character’s childhood, youth and adult life) of the conquest of the name by which that man wanted to be recognized.

Three actors give life, first to Teresa, later to Teresot (a name with special pejorative overtones that marked her adolescence and youth) and finally to Durruti, the “not at all casual” alias that she chose to join the maquis, and Florencio. The boy Adriá Nebot, the young Álex Bausá and, finally, the actor Pablo Molinero give life to a character “that the three of them have built as a team.” “Florencio was a very multifaceted character,” insists the filmmaker, who shows at the end of the film several real photographs of his physical and identity evolution. “He doesn’t fully define himself because he doesn’t know how to define himself, he even enters the maquis without ideological convictions.”

Perhaps everything is explained in a moment in the film in which a fellow guerrilla member, one afternoon watching the hours pass by in the open mountains, lends him a dictionary and tells him “there you can find all the words that exist.” “They are not all there, because I am not there.”